Olympic history: the Art Competitions

03 Jun 2018The data used in this post can be downloaded from figshare and the R code is on GitHub.

Introduction

In my last post, I charted the growth of the Olympics in terms of the number of athletes, events, and participating nations. However, the Olympics has also seen dramatic shifts in the types of events that are included. These shifts generally reflect changes in the demographics and interests of spectators, the collective desire of athletes in a particular sport to be included in the Games, and the whims of IOC members.

In some cases, the IOC’s decision about whether to include a particular sport or event in the Olympics is a statement about Olympic ideals, as understood by the IOC. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the case of the Art Competitions, which were included in the Olympics from 1912 to 1948, and included events in 5 disciplines: Architecture, Scupting, Painting, Literature, and Music. Medals were awarded to artists just like any other Olympic competition.

The ideal of including sport-inspired art alongside athletic competitions was always part of the vision that Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympics, had for the Games. He envisioned the Olympics as a multi-cultural celebration that showcased the educational value of amateur athletics for young men (and absolutely not for young women, but that’s a topic for another post). However, in 1954, the IOC concluded that art should no longer be included in the Olympics, and as a replacement, they recommended that a sports-themed exhibition be held alongside the Olympics. This tradition continues to the present day, and is known as the Cultural Olympiad.

In light of the 21st century conception of the Olympics as a Mega-World-Sports-Championship showcasing the supermen and superwomen of the world, you might be thinking, “Well of course art shouldn’t be in the Olympics, it isn’t a sport!”. On the other hand, if you are less of an athlete and more of an artist, you might find yourself balking at the idea that art could ever be included in a gladiatorial spectacle like the Olympics that presumes to crown the “best” in every category.

So you might be surprised to learn that “insufficient sportiness” or “violating the spirit of art” had nothing to do with the IOC’s decision. Rather, the IOC at the time was obsessed with the idea that Olympians should not be paid so much as a penny for their talents, and they determined that artists, who had a habit of selling their art after the Olympics, were not “amateurs”. So artists were banished to the sidelines of the Olympics, and there they have remained.

Of course, the IOC is now totally cool with Olympians making millions at their sport. Presumably, the reason why the Art Competitions haven’t been reinstated in the Olympics has more to do with insufficient sportiness and the present-day importance of television ratings. But forgotten as they may be, I find this to be a fascinating bit of history that is deserving of its own post, even if the Art Competitions make up a mere 1.3% of my data.

This post has two parts. First, I poke around in the data on the Olympic Art Competitions from 1912 to 1948. Second, I share some photos and experiences from the Pyeongchang 2018 Olympics, where I had the opportunity to see some “Olympic art” for myself and got to meet Roald Bradstock, a.k.a. the Olympic Picasso, a former Olympian and artist obsessed with keeping a place for art in the Olympics.

Data exploration: the Art Competitions

The Art Competitions included 7 Olympic Games from 1912 to 1948. Three Games during this period were skipped due to World Wars I and II (1916, 1940, and 1944).

| Year | City |

|---|---|

| 1912 | Stockholm |

| 1920 | Antwerpen |

| 1924 | Paris |

| 1928 | Amsterdam |

| 1932 | Los Angeles |

| 1936 | Berlin |

| 1948 | London |

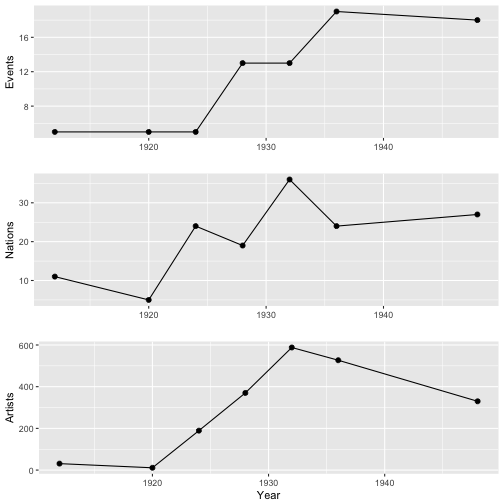

Over this period, the number of events, participating nations, and artists grew somewhat irregularly. There was a jump in the number of nations and athletes participating in 1924, and perhaps in response to this increased participation, the number of events jumped up in 1928.

The Art Competitions drew slightly more female competitors than other Olympic events during these years: 11.2% of Olympic Artists were female, as compared to 7.5% of all Olympians. However, although 11.2% of artists were women, only 7% of medals were awarded to women, and just one gold medal. Here is a table displaying all the female Art Competition medalists in history.

| Name | NOC | Year | Medal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eve-Henriette Brossin de Mre-de Polanska | FRA | 1920 | Silver |

| Dorothy Margaret Stuart Browne | GBR | 1924 | Silver |

| Laura Knight (Johnson-) | GBR | 1928 | Silver |

| Margo Sybranda Everdina Scharten-Antink | NED | 1928 | Bronze |

| Rene (Renate Alice-) Sintenis (-Weiss) | GER | 1928 | Bronze |

| Janina Konarska-Sonimska (Seideman-) | POL | 1932 | Silver |

| Ruth Blanchard Miller (-Fracker) | USA | 1932 | Silver |

| Rosamund Mary Beatrice Fletcher | GBR | 1948 | Bronze |

| va Fldes | HUN | 1948 | Bronze |

| Letitia Marion Hamilton | IRL | 1948 | Bronze |

| Aale Maria Tynni (-Pirinen, -Haavio) | FIN | 1948 | Gold |

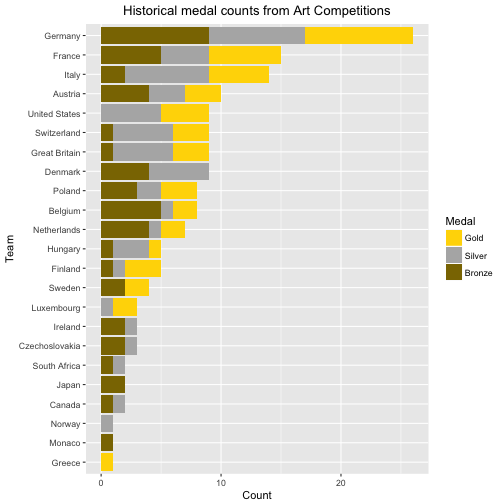

Out of 50 nations that participated in the Art Competitions, fewer than half won a medal, and over a third of all medals were awarded to artists representing just three countries: Germany, France, and Italy.

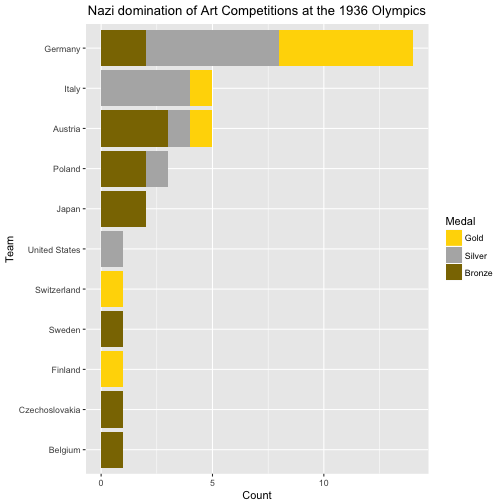

It is remarkable that Germany won the most medals in the Art Competitions between 1912 and 1948, considering that Germany was not invited to participate in 3 of the 7 Olympics during this period (they were banned from the 1920, 1924, and 1948 Olympics due to post-war politics). However, Germany made up for these absences with an especially strong showing at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, a.k.a., the Nazi Olympics, in which they won 40% of the medals in the Art Competitions and 60% of all the Art Competition medals in the country’s history.

That concludes the data exploration component of this post. In the rest of this post, I share a few of my photos and personal experiences from the Pyeongchang 2018 Olympics.

Art at Pyeongchang 2018

Although few who weren’t in Gangneung for the 2018 Pyeongchang Olympics would know about it, there was an impressive display of art along the Gangneung beach front, about a 15 minute drive from the athlete village and athletic venues. Here are some of my favorite pieces - unfortunately I don’t recall the names of the artists, but I note their countries of origin.

Obviously, this was near the top of my list: Giant skulls on the beach made from wooden planks (Korean artist).

Another favorite was this giant dragon head made from straw (Korean artist).

This tiger is pretty badass (Korean artist).

Here’s a statue of communist intellectuals gazing thoughtfully into the distance (Chinese artist).

And finally, my absolute favorite, because it makes absolutely no sense: It’s a goat with a tower of flowers for a coat… why not? (Korean artist).

The exhibit stretched on for perhaps a kilometer, and I have to say I really appreciated it. I made several trips there with friends and family, and it was a great way to spend an afternoon in a town where there wasn’t much to do if you didn’t have tickets to an event.

The Olympic Picasso

I met Roald Bradstock, a.k.a., the Olympic Picasso, at Cafe Nuts Lounge, the oddly named bar across from the Olympic Village in Gangneung, South Korea. He was having a beer by himself on the outdoor patio around 11 pm. I joined him at a table along with my friends because we couldn’t find anywhere else to sit (there was a tragic shortage of bars that stayed open past 11 near the athlete village).

I immediately recognized him from the village. I had snapped a picture of him just the other day. He was a curiosity. A flamboyantly dressed older man who hung around a trailer covered in whimsical signs, beckoning athletes to come inside and contribute some sort of art. I never saw anyone go inside.

He struck up a conversation with me and my friends. Well, I suppose it was more of a monologue - he never asked us who we were or why we were there. He told us that he was the “Olympic Picasso”, a British former Olympian who competed in the javelin throw in the 80s, and was known for decorating his own outrageous hand-painted outfits for competitions. He told us a story about the time he whipped out an American flag-themed outfit at a competition on July 4th, and the crowd went wild. He said he was at the Pyeongchang Olympics to revive a celebration of art at the Olympics. We listened to his stories politely, as groups of girls do when men insist on speaking to them at bars. After noticing that a nearby table had open up, we excused ourselves.

As soon as we were out of earshot, my friend commented dryly, “Well that was sad.” I answered, “You should see his trailer in the village. It’s pretty weird.”

I suppose the fact that it seemed so weird to me is a testament to how detached the Olympics has become from art. At the time, I had no idea that art had once been included in the Olympics as competitive events, or that the Cultural Olympiad was a thing. To me, the Olympics was about three things: sports, nationalism, and giant corporations making a lot of money. I was cynical as hell about the whole thing, but I also lacked the perspective to realize that the Olympics had ever been anything different.

I’m not trying to romanticize the past here. The Olympics has always been a complicated and fraught event, filled with contradiction and controversy, and without a unanimously agreed upon purpose. But what the Olympics is and what it ought to be are two different things.

Maybe Coubertin and the Olympic Picasso were onto something. Maybe the Olympics should be about more than medal counts and television ratings. Maybe the Olympics should be about celebrating the universal human endeavors of creating meaning and communities through art and athletics, rather than myopically celebrating the outliers of humanity and the nations that produced them.

Maybe. But how many would turn on their television for such a thing?